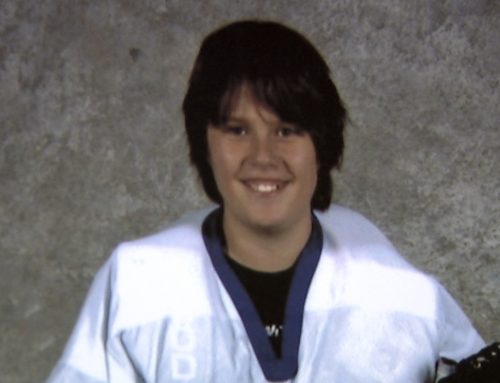

“I wanted to be a nurse and work with babies since I was a little girl. In 1990, I graduated from nursing school. I had four little babies. Until about four years ago, when this happened, my life was full of babies.” – Julie Thao

On the 4th of July, Julie Thao worked a double shift at a busy hospital where she had been a celebrated nurse for over a decade. “We were busy, and it was almost 1 AM before I was able to kind of wind down and I was too tired to drive home,” Julie recalled. Living a long way from the hospital, she decided that she was too tired to drive home, and since she needed to be back on shift at the hospital in a few hours for her day shift, she laid down in a patient room in a patient bed and tried to sleep. After some rest, Julie started her day shift. “At 9 o’clock I met the patient. She was just a young 16 year old girl and she was so scared,” Julie continued. “The plan was that they were going to break her water and start some Pitocin and she was going to deliver her baby.”

Julie followed nursing unit guidelines designed to improve readiness of patients for anesthesiologists to give an epidural injection. She adhered to a checklist of the guidelines and prepared the anesthetic medication at the same time that she had antibiotic medication ready to hang on an IV drip system. A number of systems flaws led to Julie’s absolutely predictable human error.

Julie recalled, “I got her IV, her antibiotic, and her epidural bag. Both bags had ends that received IV tubing. I had her antibiotic in my hand; I knew that. But I didn’t have her antibiotic in my hand; I had her epidural medication in my hand. And after it started running, I heard a sound and turned to her bed and she was already arresting.”

“People came to her room immediately, many, many, many people. Dozens of people who are familiar with both those medications that we used. Everyone saw that hanging there. In fact, I said, I just hung this antibiotic and I think she’s reacting to the penicillin.”

“And then somebody cleaning the room found the bag and brought it to me and they were crying and put it in my hands. And it didn’t make sense for a while and I kept looking and it just crumbled.”

Julie administered the wrong medication. Fatigue, identical medication tubing connectors, similar IV fluid bags, and a sub-optimal bar code process all collided and lead to the death of the young mother. The hospital fired Julie. She was criminally indicted. As a single mother of four and with no resources to defend herself, she had to plead to a misdemeanor to avoid prison.

The National Quality Forum Safe Practice called Care of the Caregiver is inspired by her story.

“The Julie Thao story is really a tragedy because she was hung out to dry for making a mistake which was clearly caused by a whole host of very bad systems,” explains patient safety expert Lucian Leape, MD. “She was truly the second victim in two ways, she was the victim of bad systems as well as being emotionally a second victim. She was devastated by her error as anyone would be, but in addition, she was the person who was the victim of these bad systems. And the lesson, I think is, not just that hospitals need to be responsible for their systems and fix them – which is clearly what they ought to do – but there is a second lesson here, and that is Julie Thao was fired, she was indicted, she lost her license because she was presumed to be incompetent. There’s no evidence that she was incompetent. No evidence was ever produced that she was incompetent.”

Three years after the death of Julie’s patient, the hospital published an independent study revealing that multiple systems issues contributed to setting up Julie’s error. It was an honest mistake that anyone could have made.

Never shirking her accountability for causing a death, Julie worked as a TMIT patient safety fellow to help save other lives. She helped measure lives saved and dollars invested in safety from the impact of video stories now being used in thousands of hospitals, deployed by TMIT.